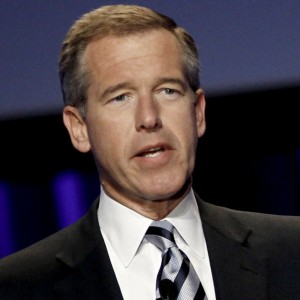

Brian Williams’ Misstep: On Keeping Apologies Real

This post originally appeared on Forbes.com

Few communication challenges can top the public apology, especially when it is forced by indisputable evidence of an embarrassing deed. What can entrepreneurs and leaders learn from NBC anchor Brian Williams and his most recent hit (or miss) in the public apology parade?

For those who’ve missed the fury, Williams has talked many times about his 2003 ride on a military helicopter during the Iraqi War. He has said the aircraft was downed by RPG (Rocket Propelled Grenade) fire. Multiple veterans have discounted the story, with vehemence. It turns out Williams was aboard the second aircraft that day, slightly behind the copter that was actually hit.

In a painful statement on social media last Friday, Jan. 30, Williams said his memory of the two copters is blurry: “The fog of memory over 12 years made me conflate the two and I apologize.” Then he made an apology Wednesday night, February 4, on the air.

For leaders in the national eye or simply in front of their teams, what is the protocol for a public apology?

No discussion of apologies is complete without observing that in the world of Internet, leaders should assume others are watching them all of the time. As simple as it sounds, most credibility disasters could be prevented by simply telling the truth, being careful of details, and pausing to think before choosing the words you will speak. As author and business expert Dr. Jeffrey Magee likes to say, “Avoid letting the first thought that comes into your head turn into the next words that fall out of your face.” But if the worst has happened, avoid these mistakes:

The mistake/excuse combination. Hilary Clinton, when being drilled by Diane Sawyer over misstatements about the lack of security surrounding the 2012 Benghazi, Libya attacks by Islamic militants said finally, “I take responsibility, but I was not making security decisions.” Bad, bad, bad. “Never attach conjunctions to responsibility taking,” notes Erik Wemple in The Washington Post. The second statement was meant to ameliorate the first, making the entire apology appear insincere.

“I’m sorry but I’m not really sorry.” Performer Justin Timberlake made this classic mistake in his apology for the infamous Janet Jackson wardrobe malfunction in 2004: “What occurred was unintentional and completely regrettable, and I apologize if you guys were offended.”

Mistake on top of mistake. Paula Deen’s scripted 2013 apology for uttering racial slurs was received so poorly she tried again. Her second try failed, too. By now the public was so distracted by Deen’s lack of apology skills the sentiment behind her missive was all but dismissed.

Passive voice. Have you noticed how politicians who apologize inevitably slip into the passive voice? Witness the King of the Non-Apology. “Mistakes were made,” was the magical construction of choice for Nixon spokesman Ron Ziegler in the Watergate era, also repeated by President Reagan when questioned about selling arms to Iran and sending the proceeds to Contras in Nicaragua. The words became a national catchphrase and eventually made their way to a book, Mistakes were made, but not by me. If a public apology is necessary, watch for passive voice, particularly with the agent (the “doer”) deleted. It’s a dodge.

Who has apologized well? One notable example is David Letterman, who publicly apologized to his wife and his Late Show staffers for having affairs with female staff members. He acknowledged that he’d been the victim of an extortion plot about his extramarital behaviors. He was frank about the fact that his actions had “hurt his wife deeply” and that he had his work cut out to make it up to her. His demeanor showed that he was genuinely sorry. Because he was able to do so with skill, he ended the statement with humor. Viewers accepted the apology. The experience seemed to have softened the comedian in a personal way as well, as he later admitted he regretted the cruelty behind jokes he’d leveled on presidential intern Monica Lewinsky, who was barely an adult when her scandalous affair with Bill Clinton occurred.

Interestingly, even Richard Nixon, after his rendition of the infamous “Mistakes were made” phrase deflected a little of his shame by responding with humor to a question about what, exactly he intended to do to right the Watergate wrong. He laughed lightly and said humbly, “It will depend on how long I’m in office.” What can we learn, then, from Williams’ Wednesday night statement?

First, the bad: On social media: “The fog of memory over 12 years made me conflate the two and I apologize.” The fog of memory made him do it? Furthermore, as author and expert Bill McGowan notes, when you’re in a tight spot, don’t try to deflect the situation with stilted language or odd words. Conflated? The word reminded McGowan of disgraced congressman Anthony Weiner who said he couldn’t claim “with certitude” that the half-nude Twitter photos were him. When NFL chairman Roger Goodell was asked if he’d seen the Ray Rice elevator video he replied that he “hadn’t been granted that opportunity.” It was an awkward way to inflate the word he meant to portray. Simply, “No.”

Then the good: The opening words of the broadcast apology were forthright: “I made a mistake in recalling the events of 12 years ago. I want to apologize. I said I was in a helicopter that was hit by RPG fire. I was instead in a following aircraft….”

Followed by the catch step: “This was a bungled attempt, by me, to thank one special veteran and by extension the brave military men and women who served everywhere, while I did not. They have my respect, and now they have my apology as well.” Note the slip into passive voice, although Williams did own the misdeed by noting the bungled attempt was “by me.”

How will it end? In Williams’ case, NBC has stayed mum. While Williams’ apology was better than most, the fact remains that he “mis-remembered” key facts (the more decorous way of saying “I forgot” and of sliding past the even more heinous possibilities of “I exaggerated” or “I lied.)” Until now, Williams’ record was stellar, but as a newscaster credibility is key. It was the fact Williams had told the story so many times and in so many versions that made witnessing veterans angry enough to set the real story straight. Perhaps Williams can re-earn at least a portion of his former credibility by being explicitly careful with factual details from now on. Perhaps he can author a book about what this lesson has taught him, or could invest his efforts in programs to support the veteran community over time.

But for communicators everywhere, the lesson is clear: Never embellish a story. Keep the details of your personal victories straight. And when a correction is called for, be forthright, be respectful and make your apology real.